The Pay-Per-Play Scheme

Something I forgot to mention in my previous post came back to me during a conversation on the train the other day. A friend of mine mentioned that Comcast wants to premiere new film releases by streaming them to subscribers on the day of release. This reminded me of some of the proposals of posters in the Quarter to Three forum thread that making video games a subscription service as a solution to large scale, peer-to-peer file sharing.

The pay-to-play scheme is a content provider's dream. Perhaps most importantly, it removes ownership completely from the consumer, and therefore, strikes out one of the content provider's greatest dislikes -- the doctrine of first sale. First sale doctrine stipulates that once a physical copy is sold that the consumer has the right to resell or give away that copy to another without compensating the content provider. First sale is a leak in the system for copyright holders. Pay-to-play schemes do this by not actually "selling" the consumer a physical product, but by instead "licensing" a copy for a one time use.

Computer software companies have been attacking the doctrine of first sale for some time now. According to the EULA (end user license agreement; that dialog box software users will check the "Yes, I agree" box without reading in order to install the software), computer software is not sold but licensed.

There have been differing court court decisions regarding first sale and software. In SoftMan Products Co. v. Adobe Systems Inc., Adobe attempted to prevent Softman from reselling their bundled software programs separately; however, the U.S. District Court for the Central District of California ruled that the terms of the EULA did not apply because Softman had never agreed to them (Softman never ran the program -- installation is the only point in which the EULA is presented); therefore, Softman maintained the right of first sale because a physical copy of the software was sold in a single transaction. In Davidson & Associates v. Internet Gateway Inc., the US District Court for the Eastern District of Missouri ruled that Internet Gateway had forfeited its first sale rights by checking the "I agree" box.

The two previously mentioned cases appear to uphold the concept that software companies can force consumers to forfeit their right to first sale in order to install their software. But the issue is not so simple because other court cases contradict this opinion. Bobbs-Merrill Co. v. Straus introduced the doctrine of first sale in 1908. In this case, the US Supreme Court ruled that the statute of the right to sell does not also grant the right to limit resale. Bauer & Cie. v. O'Donnell supported this decision and also added that simply calling a sale a license does not make it one.

While the Supreme Court decisions set the precedent of first sale doctrine, the previously mentioned lower court cases are challenging the established law. Specifically allowing software companies to force consumers into an EULA which takes away their consumer rights is only the first step towards a pay-to-play system.

Regarding the suggestions from Quarter to Three posters, the only conclusion I can draw is that many game developers and publishers would prefer this system. There are already precedents -- the most well-known being Blizzard Entertainment's World of Warcraft. World of Warcraft is an MMORPG (massively multiplayer online role-playing game) which is subscription based. Players pay a monthly flat-fee in order to play the game. Players have accepted the idea that such games will be subscription based because the game requires the use of the company servers to play. Furthermore, the game is given constant attention by the company through the release of free updates, patches, and additional content to the game. But many of the Quarter to Three posters want to place all games into a subscription system, or even a pay-to-play system.

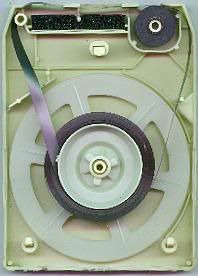

Some suggestions mimicked the MMORPG system of a monthly flat-fee. Others were for an hourly-rate, i.e., players would pay based on the number of hours logged into the game. This is basically pay-to-play lite, in that there is still an initial sale of software to the consumer, but that there will also be additional charges to play the game. The next step would be to "license" (for lack of a better term) software to consumers free of charge, but then charge the consumer for each time or for how long the game is played, or charge the consumer based on a subscription fee. This would be much like the arcades of the '70s and '80s. The end result would be that no players would actually own their games anymore.

Such systems would also require 24/7 internet connections, which means that all games would have to be played while the computer is online. Some posters pointed this out as a huge drawback that might cause many players who enjoy single-player games to object to purchasing any future games. Supporters of this system argue that it would be an effective way to combat PC game file sharing. The question is, then, would such a system do that?

If Vivendi Universal v. Jung says anything, the answer appears to be no. In this case, bnetd.org was an open-source software package reverse-engineered from Blizzard's battle.net service (Blizzard's online multiplayer service for its games using the company's servers). The software was licensed under the GNU General Public License, and provided an emulation of battle.net for players on their own privately run servers. Of note is the fact that bnetd.org circumvented Blizzard's online CD-key check, therefore allowing invalid CD-keys full access to the emulated multiplayer service. The United States District Court for the Eastern District of Missouri ruled that bnetd.org violated the DMCA (Digital Millennium Copyright Act) by circumventing the copy-protection of Blizzard's games. Despite bnetd.org being shutdown (the website is now under Blizzard's control and redirects to battle.net), other services have popped up in locations that the DMCA does not have influence.

Just as I wrote before, someone will find a way to get around any copy-protection or DRM employed in digital media. The simple fact that in order for encrypted content to be useful for consumers is to hand them the information, decoder, and key will mean that all copy-protection and DRM will always fail at some point. There will never be a hack-proof system that also makes content useful to those who the content provider is trying to prevent certain access.

There are more important reasons than the fragility of such systems for why this is a bad idea. As I have outlined before, these pay-to-play schemes designed to prevent unauthorized copying will stifle creativity and innovation. Users will no longer have access to the content in the same way they would by owning a physical copy. They will be unable to interact with the content to alter or improve upon it. Such limited access cuts a people off from their culture.

Just as the Quarter to Three posters advocate a system of pay-per-play for video games, we see the first steps towards that system with film. Comcast's move to stream new film releases could be the first step in streaming all films in the future. We already have streaming films for a fee via various On Demand services. Adding new releases to the rooster could give the film industry reason to slow, or even halt, DVD/Blu-Ray releases as some point in the future. I don't think it's that much of a stretch.

No comments:

Post a Comment